The late-night train has left Waverley Station in Edinburgh and is headed towards Glasgow Queen Street. I am slouched in my seat, flagellating myself silently for another failed Festival. Every year I go through determined this time to gorge myself on the arts. Every year I retreat feeling culturally emaciated. It's the sheer number of possibilities on offer that always paralyses me: so many exhibitions, recitals, plays, films, so many Fringe shows in out-of-the-way places that are 'stunning' and 'magical' and 'riotously funny'. I usually end up as one of an audience of nine, trying to remember where I read the review that was presumably written by the actors and wondering where the action is. It's always fun to go there but is it art? This year has been no exception.

The door to the compartment opens and two women in their 40s enter. One of them is calling to someone behind her: 'Come oan in here, hen. They're a' snobs through there.' They are followed by a girl carrying a violin-case. Throughout the long car, somnolent people quicken into apprehension, knowing that, whatever is going to happen, this is not part of the normal service of British Rail.

'Right, hen,' one woman says. 'You sit here an' gie 's a wee tune.'

The girl unlocks the lid of the case and, removing a violin from its velvet bedding, transforms it instantly to a fiddle in her hands. A spontaneous ceilidh occurs. Music, that old subversive of the senses, insinuates its way past inhibitions and darts like a pyromaniac from person to person, igniting faces into smiles. Hands clap. Heads bob rhythmically. The place is jumping. There is dancing in the aisle. Whirling there with a black man she has unceremoniously 'lifted', one of the women shouts to me: 'Ever had two Blue Lagoons? This is what they do for ye.'

The jollity continues until we have almost reached Glasgow. Then the two women go round the compartment taking a collection for the girl. She makes a nice bit of money. As we pull into Queen Street, I realise that Glasgow has had its own unofficial mini-festival.

If someone has a violin, you say to them, `Gie's a tune'. If a dignified black man is sitting on a train, you get him up to dance. If you've had a drink, you announce it to anyone who'll listen. If you think a young girl deserves some money, you take a collection from a carriageful of strangers.

The core of the onion. Does an onion have a core? This one does. I come at last to the heart of my Glasgow, boil it down and freeze it in two words: humane irreverence. Those who are, for me, the truest Glaswegians, the inheritors of the tradition, the keepers of the faith, are terrible insisters that you don't lose touch for a second with your common humanity, that you don't get above yourself. They refuse to be intimidated by professional status or reputation or attitude or name. But they can put you down with a style that almost constitutes a kindness.

A group of us are leaving Hampden after an international match. There's my son, three policemen, Sean Connery and myself. I've met Connery twice before, once when I interviewed him in the Dorchester Hotel and once, in a James Bond way, at Edinburgh Zoo, where he talked of trying to get the money together to film one of my books, Laidlaw. But with that authentic charm that he has, he has connected as if we all saw one another last week, We're going to run him to the airport to catch an early flight. We're walking and trying to find the car, which has been parked some way from the ground.

'I can't believe I'm here,' Connery says. 'I'm sitting in "Tramps" at two o'clock this morning when Rod Stewart walks in. He's chartered a private plane and why don't I come to the game. So here I am.'

It's a straight enough statement, just a genuine expression of surprise at the way things have happened. Sean Connery doesn't need to drop names, But, anyway, one of the policemen puts one quietly in the post for him.

'Aye,' he says. 'It's a small world, big yin. Ah was in a house at Muirhead at two o'clock this mornin'. It was full o' tramps as well.'

The man who says this comes, in fact, from Ayrshire but he has been a policeman in Glasgow for years, is an honorary Glaswegian. And he picked the right place to say it.

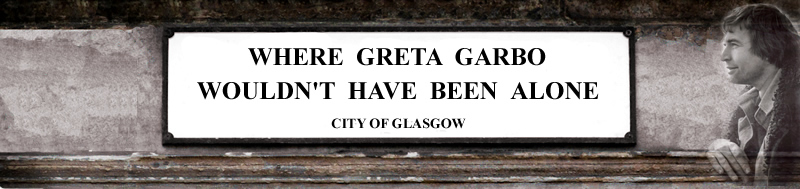

Humane irreverence: more than the big ships, Glasgow's greatest export. I just hope they don't export it all away. May the Mitchell Library, now so handsomely refurbished, always have its quota of sceptical readers finding out for themselves, noseying into things that are supposed to be none of their business. May the Citizens' Theatre and the Tron and the King's and, yea, even Scottish Opera always find among their audiences some of those perennially disgruntled faces that could be captioned: 'They ca' this art?' May the Burrell and the Glasgow Art Gallery and the Third Eye Centre always have their equivalent of the wee man I once saw standing before 'Le Christ', seeming to defy Salvador Dali to justify himself and shaking his head and glancing round, as if looking for support. For if they go, Glasgow, except for the bricks, goes with them.

They — not the image-makers, not the bright-eyed entrepreneurs, not those who know the city as a taxi-ride between a theatre and a wine-bar, not those who see it as Edinburgh on the Clyde, not the literary cliques, not those who apply the word 'renaissance' to a handful of movies and a few books of poetry and some novels and plays — they are the heart of Glasgow: the quizzical starers, the cocky walkers, the chic girls who don't see a phoney accent as an essential accessory of attractiveness, the askers of questions where none was expected, the dancers on the train, the strikers-up of unsolicited conversations, the welcomers of strangers, the deliverers of deadly lines in most unlikely places, the people fighting decency's rearguard action in Possil, the unpretentious, the unintimidated. Glasgow belongs to them.

|